- Why second opinions often disappoint

- What a second opinion is actually for

- The cost of unstructured medical data

- What information actually matters for a second opinion

- How preparation changes the conversation

- A practical way to organize medical data

- What this does not solve

- Responsibility and ownership of information

- When preparation matters most

Why second opinions often disappoint

People look for a second opinion when something still feels unclear: the explanation did not fully connect the dots, the plan feels premature, or the situation is more complex than a single visit can hold.

When the second opinion disappoints, it is easy to assume it is about conflicting expertise. More often, it is about missing context. The second clinician is handed fragments: a few lab values, a short summary, maybe a medication list, but not the sequence of events that made those data points meaningful.

In that situation, the appointment becomes a reconstruction task:

- What happened first?

- What changed after which test?

- What was ruled out, and on what basis?

- What is still unknown?

If the foundation is incomplete, the safest output is often cautious and general. That can feel like a non-answer, even when the clinician is doing the reasonable thing given the inputs.

What a second opinion is actually for

A second opinion is not mainly about getting a different conclusion. It is about stress-testing the reasoning behind the first one.

For that to work, the second clinician needs to see:

- what information was available at the time,

- what assumptions were made (explicitly or implicitly),

- what alternatives were considered or ruled out,

- what uncertainty remains and why.

Without this, the second opinion is forced into guesswork. With it, the conversation can focus on what you actually need: priorities, trade-offs, and the smallest next steps that reduce uncertainty.

The cost of unstructured medical data

Medical data almost always accumulates in pieces. Lab results sit in one system, imaging reports in another, clinic notes elsewhere, and symptoms mostly in memory. Over months, the narrative gets diluted.

When data is unstructured:

- timelines blur (what was before vs after),

- results get interpreted in isolation,

- past decisions become hard to evaluate,

- constraints get missed (prior reactions, comorbidities, medications, prior episodes).

This is not just an inconvenience. It can degrade clinical reasoning. When the picture is incomplete, the cost of being wrong is higher, so conclusions tend to be conservative, and recommendations may become broader or less specific.

What information actually matters for a second opinion

More documents are not automatically better. What helps is a structure that lets someone new to the case orient quickly and verify the critical facts.

Useful information usually falls into four groups:

- timeline: when symptoms started, how they evolved, what changed, and what triggered changes (new medication, infection, travel, procedure),

- key findings: what tests were done, when, and what the relevant results were (including reference ranges when available),

- context: diagnoses and relevant medical history, current medications and supplements, allergies, prior similar episodes, and any relevant family history,

- decisions so far: what was recommended, what was tried, what changed, and what the reasoning seemed to be.

Aim for "reviewable", not "impressive". The goal is not to persuade the second clinician. It is to let them reason independently from the same base and to make it easy to validate the story against the records.

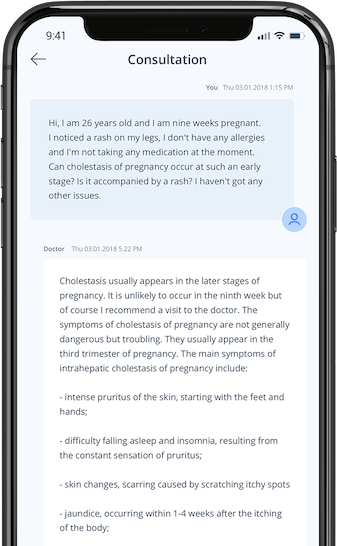

How preparation changes the conversation

With a prepared record, the tone changes quickly.

Instead of spending the first half of the visit collecting missing basics, the clinician can spend time on interpretation:

- what carries the most weight,

- what is still ambiguous,

- which alternative explanations remain plausible,

- what would change the decision either way.

This shifts the interaction from information gathering to decision support. It also makes disagreement useful: if the clinician reaches a different conclusion, they can point to the specific assumption or piece of evidence where their reasoning diverges.

A practical way to organize medical data

You do not need a perfect system. You need a usable one that can be scanned in minutes.

A simple structure that works in most cases:

- brief summary of the main issue (one paragraph: what is happening and what decision is pending),

- symptom timeline (dated bullet points or short sentences),

- list of key tests with dates and relevant results (grouped by type: labs, imaging, pathology, procedures),

- current medications and relevant history (only what affects interpretation),

- the specific question you want help answering (one or two sentences).

Keep it modest. Add detail only when it changes interpretation. If you have multiple conditions, separate them clearly so the case does not read like one long, undifferentiated story.

What this does not solve

Good preparation does not guarantee a clean answer. Some problems remain uncertain even with excellent records. Sometimes the best output is still "we cannot conclude yet", especially early in a workup.

What preparation does is remove avoidable ambiguity. It ensures that uncertainty comes from the medical problem itself, not from missing dates, missing results, or an unclear sequence of events.

Responsibility and ownership of information

Preparing medical data is not doing the clinician’s job. It is taking ownership of your side of the process.

Clinicians bring training and judgment. Patients bring lived experience, observations, and continuity across systems. When those inputs are structured and accessible, reasoning improves on both sides.

If you are unsure how to frame your question alongside that information, this guide on writing clear medical questions may help.

If you are comparing automated tools with clinical interpretation, this article on symptom checkers versus asking a doctor provides useful context.

When preparation matters most

Preparation becomes especially important when:

- the situation is complex or evolving,

- multiple clinicians are involved,

- decisions have long-term consequences,

- you are weighing whether to proceed, wait, or investigate further.

In these cases, clarity is not a convenience. It is part of the decision itself.